Spanish Influenza, 1918-1919

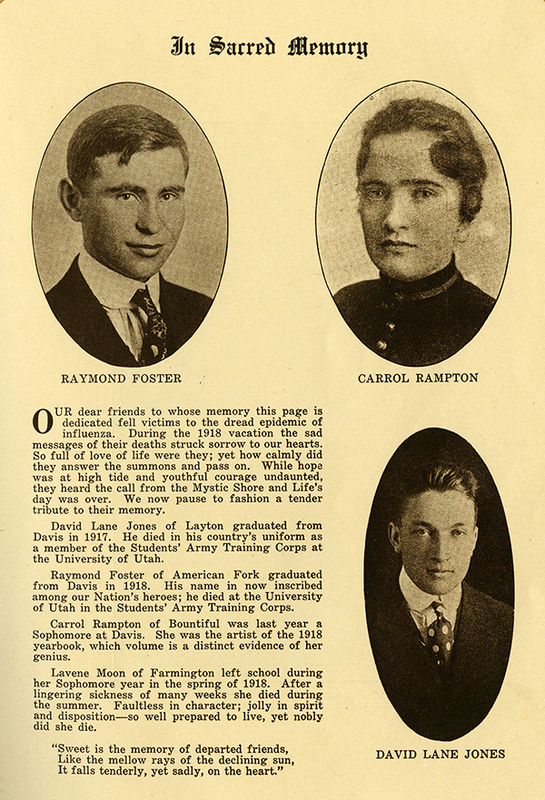

In September of 1918, soldiers returning from Europe brought the Spanish influenza with them, and soon the country was consumed by a pandemic more severe than any seen since the bubonic plague in the 1400s. On October 4 the first cases of Spanish Influenza hit Salt Lake City. One week later, over 300 cases were identified and cities in Utah went into quarantine cancelling schools, church meetings, and all public gatherings.

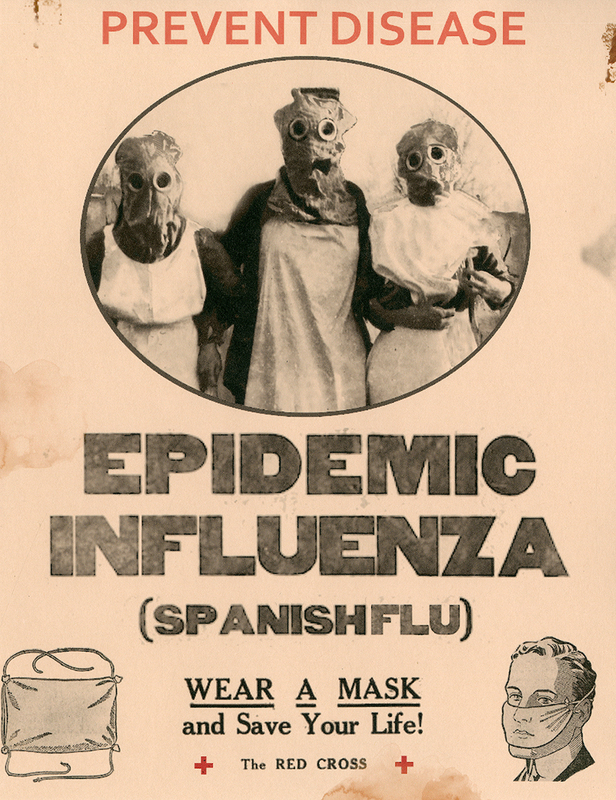

An emergency hospital was established in Ogden at the First Congregational Church with ten nurses on staff. A statewide order for the wearing of masks went into effect on October 26. Patients, medical staff, and everyone in offices, workshops, and public places were all required to wear masks. The masks were to be worn over the nose and mouth and cleaned every 24 hours by boiling them for 20 minutes. Those who failed to comply were fined $10.

The Red Cross started making masks for the public, but struggled to keep up with demand. The Japanese women’s association, Ha ha no kai, aided the Red Cross by making 500 gauze masks. Instructions were also provided in newspapers for individuals to make their own masks.

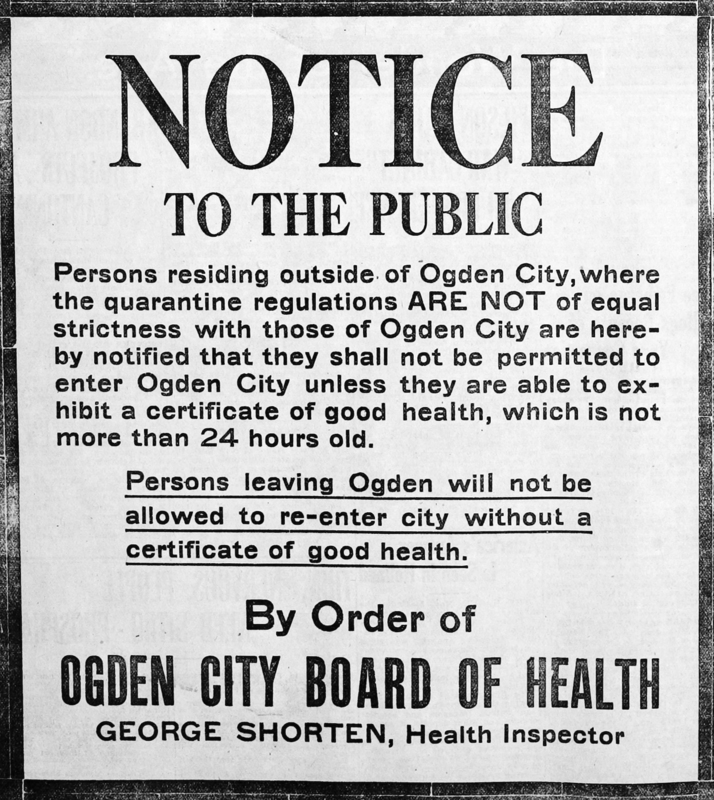

In early December, after Salt Lake City officials decided to lift restrictions on gatherings, Ogden officials issued an order to quarantine the city. Every traveler from outside the city was required to have a certificate of clean health from the health board. Schoolteachers were sent to railway stations and roads entering Ogden to check for the certificates. They were also sent to homes to ensure that anyone with influenza was quarantining properly. The strict quarantine order upset Salt Lake officials, but Ogden citizens were determined to protect their city.

Vaccines arrived by December 12, and the reopening of the city began by the end of the year. Schools reopened December 30 with 90% attendance and doctors on hand to examine the children. By spring the disease had mostly run its course, but nearly 4% of those who contracted the disease had died. This meant Utah’s death rate was third in the nation.